Still Quiet

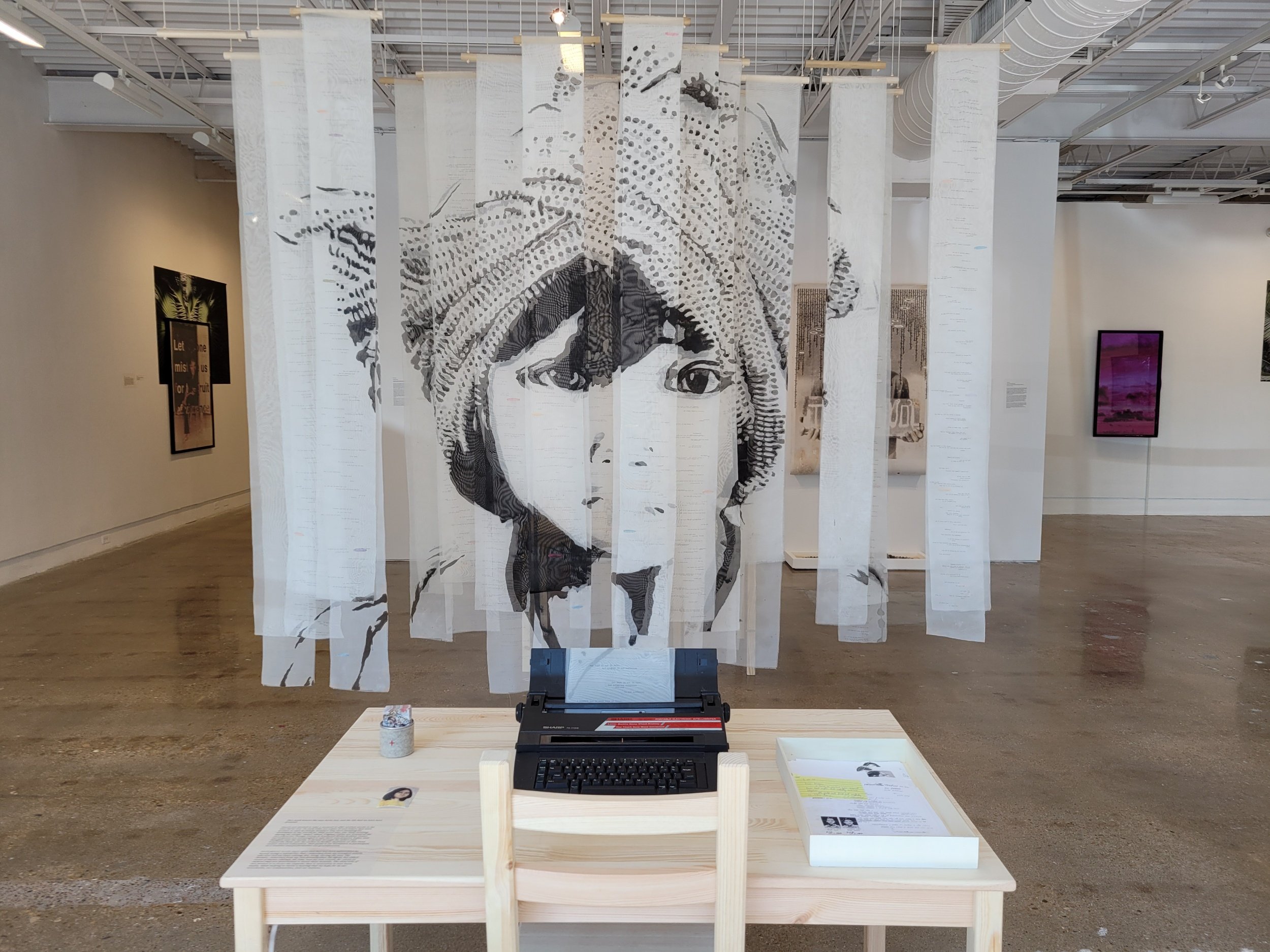

Still Quiet, 2023. Ink, gesso, graphite, holy water, tears, and thread inherited from my late grandmother, Bà Ngoại, late great auntie, Bà Tiên, and my late cousin, Bi, on chiffon; copies of the Paul Tran Files and typewriters on wooden tables, 9 x 9’ portrait, installation dimensions variable. Commissioned by Fort Worth Contemporary Arts, Texas Christian University, Fort Worth, TX.

From 1975 to 1979, my father-in-law, Phơưl Vân Thạch, led his family out of the war in Việt Nam on foot. Upon crossing the border, they found themselves faltering into another war as the Khmer Rouge devastated Kampuchea, or present-day Cambodia. Many of his family members survived, arriving in Thailand, where they were received at the refugee camp, feet bloodied, ankles swollen. Bác Phơưl’s eldest daughter was not one of these survivors.

Living with a trauma so great, Hiền’s parents seldom spoke about Chị Dung. But throughout his childhood, by piecing together fragments of their quiet conversation, Hiền was confronted with the death of his eldest sister. In the turmoil of war, no documents or photos of Chị Dung survived. And because Hiền was an infant when we lost her, he has no recollection. This piece is an attempt to capture the child that we imagine Chị Dung to be—innocent and beautiful, unknowing and tender-eyed, but perhaps somewhat aware of what was to become of the nation they once knew as home.

Still Quiet is a continuation of thought that stems from the Quiet installation (2015) that I created in reverence of lives lost during the years of war in Việt Nam, and its aftermath of longing and bereaving—these voices that continue to call out to us. While Still Quiet holds this same reverence, it further speaks on the silences that remain in the wake of trauma and immense grief that inflame when loved ones perish under the wreckage of war. Donning the traditional Khmer krama, Chị Dung’s fragmented portrait speaks on the fractures that can be caused by great loss, the chiffon portraying the fragility of life. This project honors the lives of the innocent, in life and in death.

Guests are invited to take a moment to offer written words to the ones we’ve lost. On each table are copies of real letters that were written in 1996 by family members who were pleading for assistance in the search for their loved ones who went missing during the escape—letters whose original copies are housed at the UCI Libraries Orange County & Southeast Asian Archive Center. Participants are encouraged to type their own prayers, hopes, and thoughts onto the textile, or peruse through the letters and transcribe them onto the sashes to further meditate on this lived and/or shared tribulation. Still Quiet is an invitation to participate in a creative and performative act of compassion.

Participants’ words layer upon my own words that were inked from a typewriter that I inherited from my youngest auntie, who also lost an older sibling, Bác Hưng, during the war. The threads—inherited from my late grandmother, Bà Ngoại, her eldest sister of twelve siblings, Bà Tiên, and my late cousin, Bi—serve as sutures that are determined to mend these wounds. The chief aim of this project is to foster the empathy that is necessary to love more deeply, while helping to incite a healing that we hope for in our households, our communities, and our nations.

Ghostly sashes suspend from above, representing traditional Vietnamese mourning bands that are worn during funerary rituals. They serve as an ephemeral veil that is cast between two seated participants as they come face to face with each other, with Chị Dung, with innocent children everywhere, and with the ones that we carry in our hearts still.

Still quiet at the 2025 Cambodian American Studies Conference, Santa clara county office of education, san josé, ca