Interlude

/I felt strong. I had been proactive. I was hopeful. Given severe personal circumstances, I felt bent but supported, fractured but productive, having just returned from a most encouraging springtime visit with university students who flanked the country. Together, on both coasts, we gleaned what history had left for us to examine and built bridges upon which we could meet and share our findings. This warming experience with the collective body lingered with me, and I was anxious to see how this inspiration would imprint the work once I returned to the studio.

But against my fantastic expectations, the studio pooled with an incongruous medley composed from recent in-depth conversations. On war and forgiveness. On the injustice that devastates families. On dark histories and promising futures. On the lingering residue of fear and how love and community can help rinse it away. On the horrors that we’ve witnessed and how art undeniably helps alleviate the heart from further shredding.

I felt like I had been swallowed up whole and dragged into the belly of confusion (both by life and by art; there is little difference between the two). It wasn’t that I hadn’t ideas from which to draw; neither was I sinking into a space where fear, resentment, and doubt merges. (I’ve waded tirelessly in that muddy sea times before. This wasn’t it. At least, I don’t think it was.)

I could barely contain it all, and even worse, I couldn’t find the suitable expression to purge.

I began multiple projects with great fervor, but they spoke in incomprehensible tones and tenors that steered me even deeper into uncertainty. Perhaps it was because I was still transitioning back into quiet, still processing the good and dense and constant mind and heart activity during the previous weeks in Seattle and Cambridge. Everything that I had produced in the first two weeks upon my return from fellowship was essentially part of a disparate collection of busy work. My hands were grateful to be back in the sanctuary and were satisfied with pursuing all that they could handle. But my heart was tangled and my mind muddled, and they rendered a faltering performance, demonstrated by the littering of material that covered the walls and tables, like some mad scientist’s lab, sans hypotheses of any kind.

: :

I began four 48 x 36” oil paintings, inspired by shadows cast upon the waters below me as I flew from Seattle back to Orange County—these shadows that can sometimes help us more clearly see what dwells underneath the water’s surface below the layers of sediment. I thought about how the shadows cast upon life also have a way of leading us into knowledge and wisdom…but only if we can stand steadily in the sweeping stream and be patient enough to garner what will be offered to us in due time.

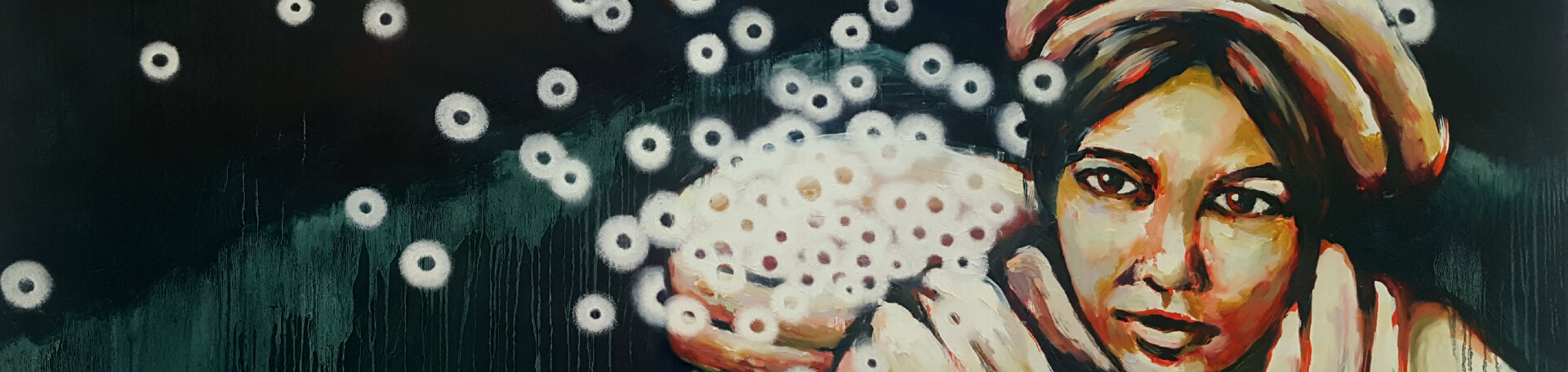

As these first passes stood in the corner, dripping with a somber yellow ochre, an even larger painting arose, surging with too many questions about the children who have been forced onto these threatening seas and treacherous roads, pried hastily from their parents, detained, destitute, and alone amidst the multitude. I wept for the parents who continue seeking inclusion, justice, answers, and liberation for their families and for their people.

And while considering the children, I reflected on We, the descendants.

On Thanksgiving of 2015, I lay out a mosaic of papers upon my uncle’s wooden table. I was still coasting on the excitement of having completed a portrait of Bà Ngoại that had been drawn with my fingerprints, inspired by the thumbprints stamped upon the back of her Việt Nam identification card. I was compelled to collect the fingerprints of other family members, even though I was unsure of where this might lead.

After a four-year incubation period, I reexamined these vestiges. I studied the movement of line in each individual mark, unique and graceful, squeezed neatly into a small, imperfect seed. Then I tethered them together with a lifeline.

Fingerprints collected from three generations

I revisited my pebble collection, satisfied by the sound of their hollow knocks as I poured them out of a pickle jar. They scraped together in my palms, the grooves of my fingerprints gripping any slight grit that hadn’t yet been smoothed down by the waters that shaped them. I painted some of them gold and wrapped others with crimson thread—the lifeline from which we draw sustenance, the blood that binds us to the strength that exists within ourselves and the pulsing spirit of our ancestors. Then, I nestled some of them into a bed of rice so that they could lay comfortably beside one another while I figured out where this all might be going.

After some time, this all began feeling like play and this play made things feel less doubtful. A found jaw bone arrived on the scene. Then a seed pod. Lined and spotted leaves and kindred feather. And more stones. Always more stones.

After she had passed, I found this lovely fragment of earth that Belle had begun anointing. The river stone sat on her studio floor, peeking timidly from behind the foot of her work table. I painted the break. And as I coated these rough surfaces with paint that I had inherited from her collection, I squinted at the vibrancy of gold against stone against the delicate text that curved with the natural grace of her hand. And while I was at it, I painted the break in one of my found gator vertebrae, just to see what might arise from these golden stones and broken bones. (Girl—look. Still golden.)

I reexamined the extensive collection of Bà Ngoại’s letters that I promised her would remain unread. And then, in the madness of this creative rant, I rolled them into tight little scrolls and tucked them into cocoons woven by Vietnamese silkworms, like delicate vaults for these sensitive secrets that I vowed to protect.

Springing from this notion, I began writing letters. Lots of letters. A letter to my mother. A letter to Bà Ngoại. A letter to my husband. A letter to fear itself. Letters stacked upon letters. Letters to God that interlaced themselves into these letters. On paper. On vellum. On cotton. With ink. With paint. With graphite. Letters to be read. Letters to remain unread. I even experimented with creating my own cryptography, twisting and bending the characters from the Roman alphabet, to be sure that they remained unread.

It began feeling like the work stemmed from one to the next, after all. Belle and I would often speak on the struggle within our breath of mediums. Through our lengthy conversations, we’d confront the chattering noise that would peek its persistent head into our studios from time to time. We’d discuss how our body of work comprises all of the material that emerges from our hands, and that whether or not we recognized it immediately, the work does indeed weave its way back into itself. We’d confirm for one another and for ourselves that we needed to trust in curiosity, process, and inspiration—that it would all coalesce into something that would engrave itself into the timeline of our Life and Art practice. God, I love that girl.

I felt like I had been drifting aimlessly through string and stone and scattered substance, so I decided to press through this suspension of any entirely recognizable progress by returning to what I knew best—drawing—the foundation upon which my art practice had been raised. Perhaps it would help me regain some confidence and lead me toward some discernible direction.

I remember sitting on the cool hardwood floor of Bà Ngoại’s bedroom when I first came across this portrait of my mother at age fourteen. Face like mine. Mine in hers. When I was younger, people used to tell me that I looked like my father. As I grew into my teen years, they began telling me that I looked like my mother, that my voice and mannerisms echoed her own. I’m not sure that I ever truly saw what they saw until I discovered this photo in one of Bà Ngoại’s albums, sandwiched between the dozen others that stood neatly in her closet above her collection of woolen blazers and áo dài.

So, I began with a small drawing of my mother.

And this led me to working on smaller, more manageable pieces.

And that’s all that I could hope for—something manageable.

And as I buông xả and let go, my hands vigorously leaped from one piece to the next as they informed one another. They stitched themselves together in memory, method, and motif. At first, I hadn’t recognized this as a cohesive collection of works, given each one’s divergent nature. Instead, I approached this as a critical endeavor to push my way through this block* that I had been laboring through.

*I’ve heard of this thing that other creatives might define as a block, but I personally don’t feel like the word sufficiently describes the complexities of this episode. It is not the lack of inspiration, but rather an overabundance of urgent thoughts that swell anxiously as they wait to emerge. The vessel that holds them has an opening that can only pour out a few at a time. I liken it unto a sluggish seeping of inspiration that wrestles with finding the right language with which to assert itself.

Soon, it runneth over. The wall was quilted with these fragments that began as play, but had somehow become much more with every mark.

Mother came first. Then her mother. Then her mother’s mother. Then her mother’s mother’s mother. I arrived last as daughter in the work as in lineage. I burned candles for them as I peered into the eyes of these women who gave the life that gave life. I spilled the wax onto the paper to document the time. I mourned for them, I honored them, I delivered them from past into present, and then back into past. Thirty-six of these pieces came to life, each telling the relational stories that appeared on these mixed media pages.

From a fettering suspension in the studio, the Mẹ Ơi collection was born out of a desire to break through the lull by remaining obedient to the process by simply keeping my hands active. This discomforting experience renewed my faith in the idea that these intermissions are good for us. I liken them unto a training of sorts—an effort of the body and fingers, an awakening of the different facets of our imagination, an exertion of thought, an invitation to play with a volume of materials in a vocabulary of methods, a nudging for us listen to how they might converse, an experiment with matter as an exercise of mind and will.

It’s a wonder why I don’t welcome more of this. Perhaps, it stems from a fear of not having enough time. I’ve come to recognize that these interludes offer clues toward the more serious work (whatever this means)—the work that clutches our souls and wrings out the words, the images, the knowing that was within us all along. I want to remember this so that I can refer back to it when it arises again. (Honestly, how would I even manage a continuous stream of the more serious work, anyway? One might find me coiled in a bed of ash and stone on the studio floor. These respites may help save me from myself as I undertake the dense matters that often influence my work.) I tell myself:

The time I have is short. There is no time for shallow matters.

Except that none of this is shallow. These moments of pause invite us into a place of profound depth if we agree to wander and wade through the unknown and toward a skewed horizon. It summons us into a trust with the uneven terrain that will lead us to a banquet of creative wealth and wisdom.

Herein, lies our salvation.